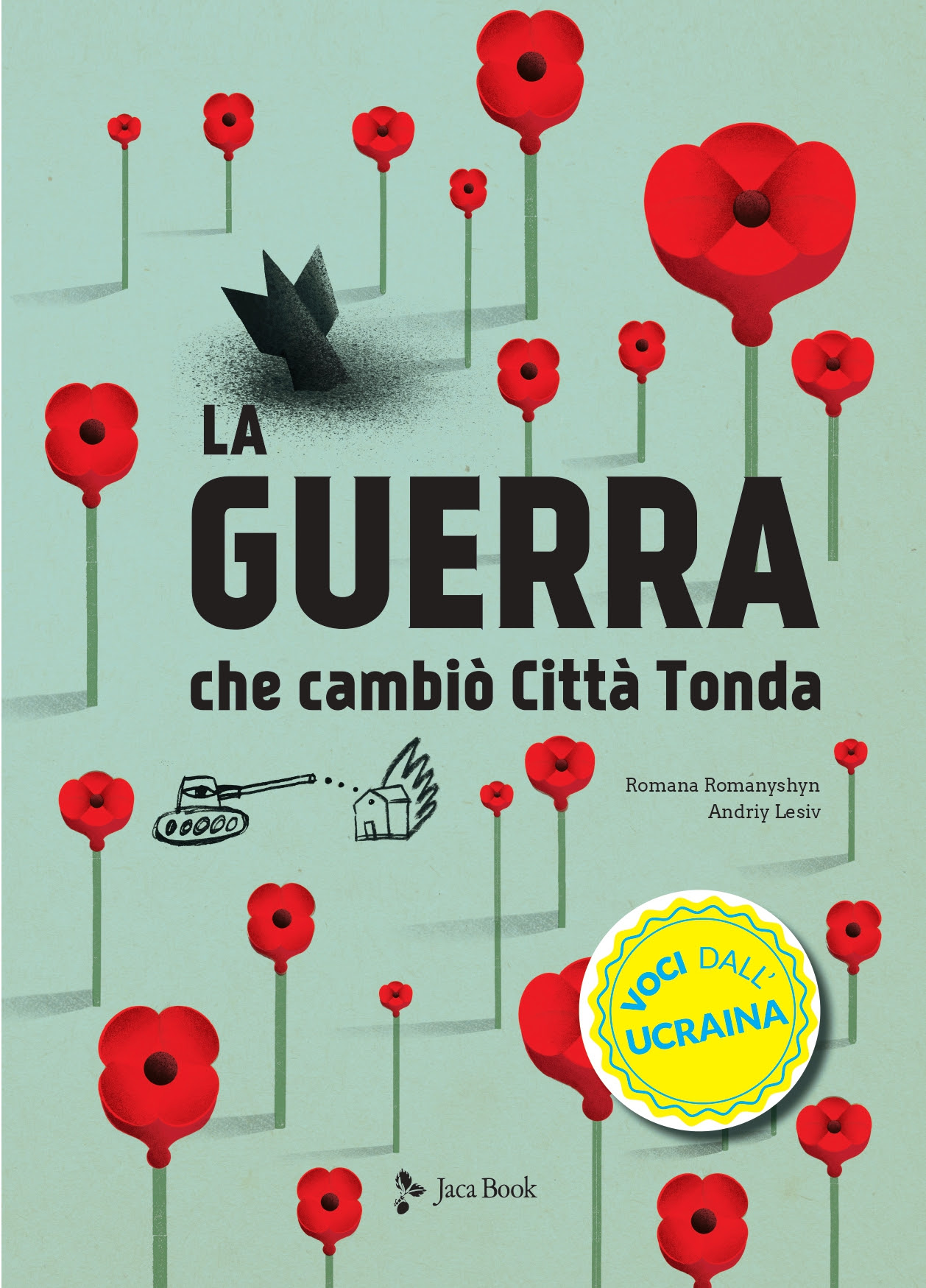

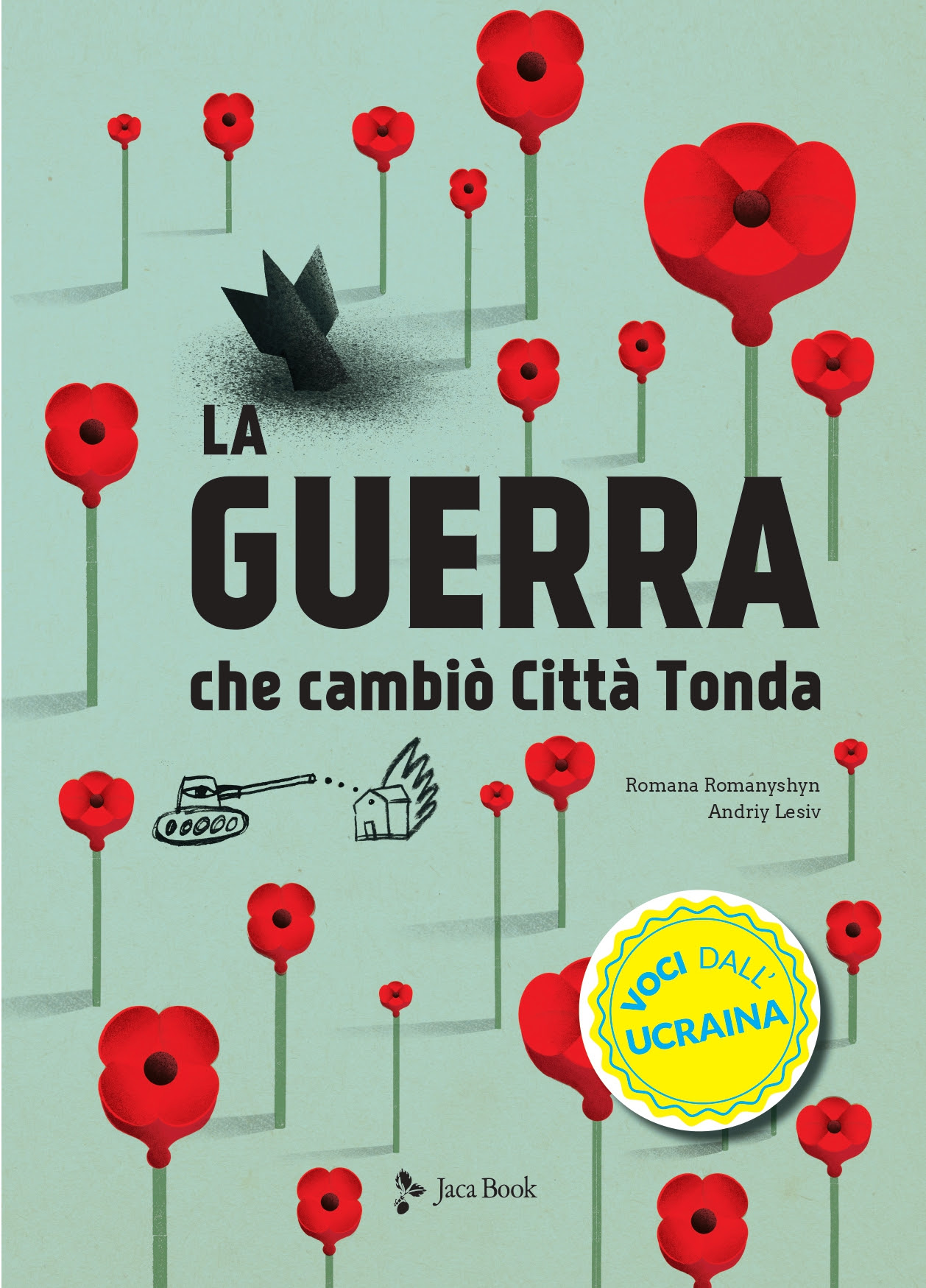

La guerra in Ucraina raccontata ai bambini

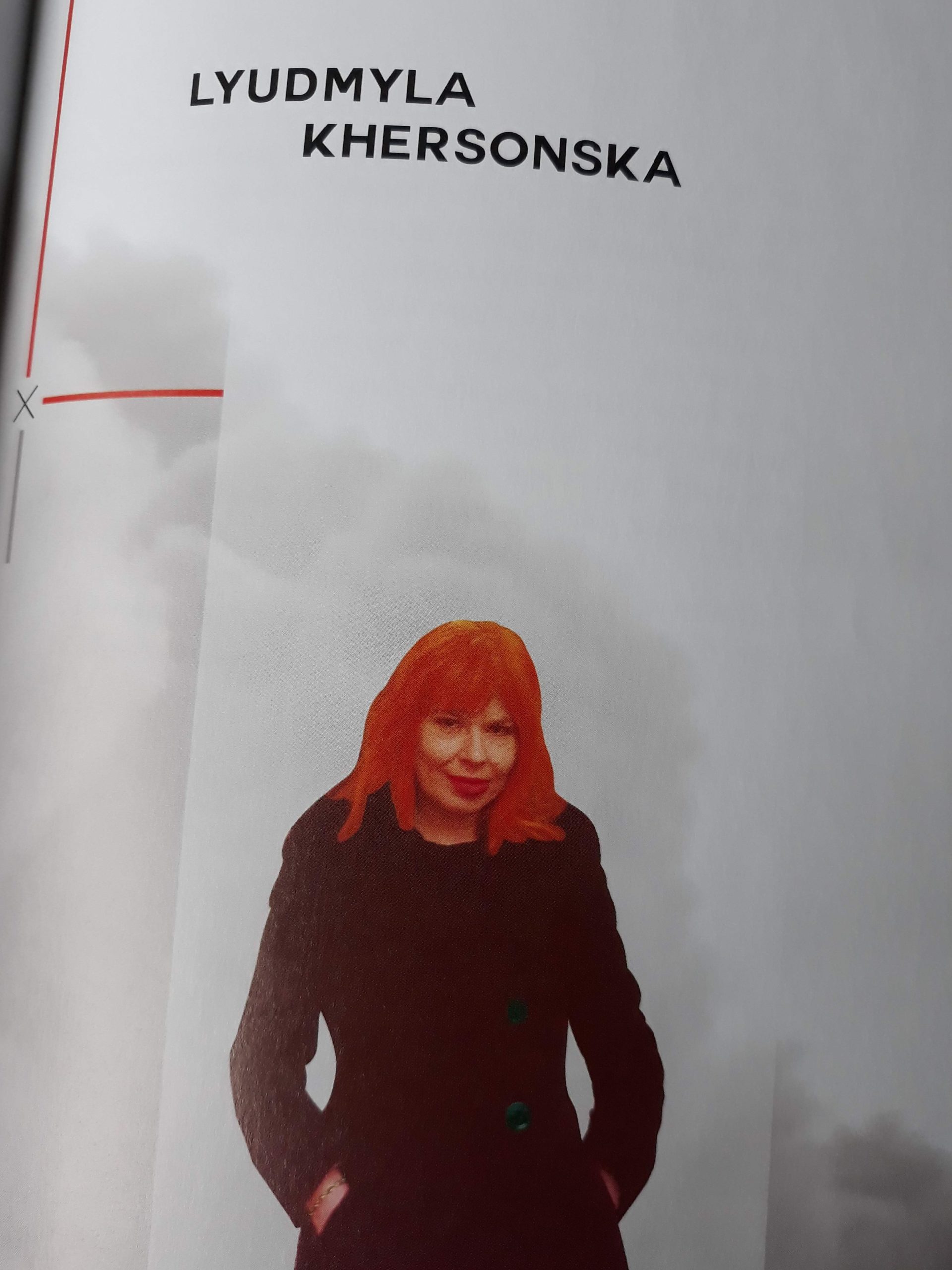

Una storia scritta da Romana Romanyshyn e Andriy Lesiv. Una coppia nel lavoro (e nella vita), ha creato l’atelier «Agrafka» a Leopoli, in Ucraina, realizzando in pochi anni progetti innovativi acquisiti da case editrici di tutto il mondo.

Jaca Book, pubblicando Forte, piano, in un sussurro, (vincitore del Premio Andersen 2019 per la categoria divulgazione scientifica) e Vedo, non vedo, stravedo (Bologna Ragazzi Award 2018) ha deciso di “adottarli” per portare anche in Italia i loro libri pluripremiati. In particolare Numeri, stelle e mucche di mare, premio «Opera prima» alla Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2014 e La guerra che cambiò Città Tonda, premio «New Horizons» alla stessa manifestazione nel 2015. Per Jaca Book hanno pubblicato anche La casetta degli animali (2018) La mia casa, le mie cose (2019) e In viaggio per il mondo (2021), vincitore dell’Argento del prestigioso «European Design Awards» 2021, nella categoria “Libri e illustrazioni editoriali”. I loro progetti si contraddistinguono per l’uso sapiente di tecniche e stili, uniti a una narrazione che incuriosisce e affascina i lettori.

Intervista di Luigia Sorrentino

Traduzione dall’inglese all’italiano di Giorgia Sensi

The war that changed Rondo.

Romana Romanyshyn and Andriy Lesiv: why did you feel the need to tell children about the war with an illustrated story?

“We had never actually planned to create a picture book for children about war, but reality in our country changed things. It all started with the Revolution of Dignity at the end of 2013, then the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and Russian invasion in East Ukraine. The war had started. Thousands of victims and broken lives. At that moment we were all unprepared and vulnerable, but determined. Many of our friends were mobilized for military service. We couldn’t stay calm and we had to react in some way. Often, parents don’t know how to explain to their children what war is and why it has come to their homes. We decided to create a picture book which could be the starting point for such a sincere talk between children and their parents about what is going on. It had to be a book like therapy, when you talk about your fears first and then stop being afraid. We also noticed that there is still no children’s book about war which would show our own experience, because every country has its own story of surviving and fighting. Yes, there are many great children’s books about war, but they are about someone else’s experience, they are from a distance, not about how we feel it”.

“La guerra che cambiò Città Tonda”. Romana Romanyshyn e Andriy Lesiv: perché avete sentito il bisogno di raccontare la guerra ai bambini con una storia illustrata?

“Non avevamo mai davvero pensato di creare un libro illustrato per bambini sulla guerra, ma la realtà del nostro paese ha cambiato le cose. Tutto è cominciato con la Revolution of Dignity alla fine del 2013, poi l’annessione della Crimea nel marzo 2014 e l’invasione russa dell’Ucraina orientale. Era cominciata la guerra. Migliaia di vittime e vite spezzate. In quel momento eravamo tutti impreparati e vulnerabili, ma determinati. Molti dei nostri amici furono richiamati per il servizio militare. Non potevamo restare fermi, dovevamo reagire in qualche modo. Spesso i genitori non sanno spiegare ai figli cos’è la guerra, e perché è entrata nelle loro case. Decidemmo di creare un libro illustrato che costituisse il punto di partenza per un discorso franco tra genitori e figli su ciò che stava succedendo. Doveva essere un libro-terapia, dove prima parli delle tue paure e poi smetti di avere paura. Notammo anche che non c’è un libro sulla guerra per bambini che mostrasse la nostra esperienza, perché ogni paese ha la sua storia di lotta e di sopravvivenza. Sì, ci sono molti grandi libri per bambini sulla guerra, ma raccontano l’esperienza di qualcun altro, sono distanti, non parlano di come stiamo noi”.

When was the book published in Ukraine and what kind of diffusion did it have among Ukrainian children?

“Luckily we have a great common understanding with our Ukrainian publisher Old Lion and they totally supported us with the idea to publish a picture book about war. So the book was first published at the end of 2014. It had few additional editions during these years. We received tons of reviews, letters, drawings from children and their parents”.

Quando è stato pubblicato il libro in Ucraina e che diffusione ha avuto tra i bambini ucraini?

“Per fortuna abbiamo una grande sintonia con il nostro editore ucraino Old Lion, che ha sostenuto pienamente la nostra idea di pubblicare un libro illustrato sulla guerra. Così il libro uscì per la prima volta alla fine del 2014. E in questi anni ha avuto diverse ristampe. Abbiamo ricevuto tonnellate di recensioni, lettere, disegni dai bambini e dai loro genitori”.

Why did you decide to tell the children the story of Danko, Fabian, Zirka?

“The base of every story is a character. We had to make our characters not artificial, but very authentic. We created characters which embody the feeling of every Ukrainian. We all felt very fragile and vulnerable, but strong and unbreakable. That’s why characters in our story are made with fragile materials, easy to destroy – glass, paper, balloon. But despite their fragility they fight, resist and protect their home”.

Perché avete deciso di raccontare ai bambini la storia di Danco, Fabian, Zirka?

“Alla base di ogni racconto c’è un personaggio. I nostri personaggi li dovevamo rendere davvero autentici, non artificiali. Abbiamo creato personaggi che incarnano il sentimento di ogni ucraino. Ci sentivamo tutti molto fragili e vulnerabili, ma forti e indistruttibili. Ecco perché i personaggi della nostra storia sono fatti di materiali fragili, facili da distruggere – vetro, carta, palloncini. Ma nonostante la fragilità, loro combattono, resistono e difendono le loro case”.

In your story there are sentences like: “the war is coming to our city”, “The war spares no one”, “The war has no heart”. Were these the stories you heard from your grandparents when you were children?

“Yes, of course we heard a lot of terrifying stories about war from our grandparents. And so many stories they did not want to share with us. Our grandparents spent 12 years in Gulag repressed by Stalin’s regime. They really hoped that our generation would not suffer from russians anymore. But we see that now the grandchildren of our grandparent’s enslavers are trying to kill us. And it’s a really unbelievable fact that in the 21th century, the time of technological progress, when we all have free access to information, Russia is still acting like 100 years ago, they still want to destroy and enslave, they still live in a dark past. And we fight for the future”.

Nella vostra storia ci sono frasi come: “la guerra sta arrivando in città”, “la guerra non risparmia nessuno”, “la guerra è senza cuore”. Queste frasi le sentivate dai vostri nonni quando eravate bambini?

“Sì, naturalmente abbiamo ascoltato tante storie terrificanti sulla guerra dai nostri nonni. E molte non le volevano condividere con noi. I nostri nonni hanno passato 12 anni in un Gulag durante il regime di Stalin. Speravano sinceramente che la nostra generazione non avrebbe più sofferto a causa dei russi. Ma ora vediamo che i nipoti di chi ha schiavizzato i nostri nonni stanno cercando di ucciderci. Ed è davvero incredibile che nel XXI secolo, il secolo del progresso tecnologico, quando tutti abbiamo accesso alle informazioni, la Russia si stia comportando come 100 anni fa: vogliono distruggere e schiavizzare, vivono ancora in un passato oscuro. E noi combattiamo per il futuro”.

The three protagonists manage to defeat the war by building a machine for the light and this machine scares the War. If we were to rewrite this tale today, what should we add? Which words?

“We’re not sure we should rewrite the story. The machine for creating the light is a symbol of unity, where everyone turns a small wheel so the machine works, symbol of organized resistance and coordination. Today it is a symbol of unity of the world, when many countries join their efforts to stop the aggression. Everybody is trying to help.

To get through these dark times, full of fear, anger and loss, we all need a ray of light, of hope. We can not hide a horrific truth from children anymore. The reality is much more horrible than any book. But we can’t stop telling and reading stories, even hiding in bomb shelters, even flleeing from our attacked homes. In our story we highlighted the strongest advantages of Ukrainian people – courage and unity”.

I tre protagonisti riescono a vincere la guerra costruendo una macchina per la luce, e la macchina spaventa la Guerra. Se riscrivessimo questa storia oggi, cosa dovremmo aggiungere? Quali parole?

“Non siamo sicuri sulla necessità di riscrivere la storia. La macchina per creare luce è un simbolo di unità, dove ciascuno gira una piccola manovella per far funzionare la macchina, simbolo di resistenza organizzata e coordinazione. Oggi è il simbolo dell’unità del mondo, quando molti paesi uniscono i loro sforzi per fermare l’aggressione. Tutti cercano di aiutare.

Per superare questi tempi bui, pieni di paura, di rabbia e di lutto, abbiamo tutti bisogno di un raggio di luce, di speranza. Non possiamo più nascondere ai bambini una verità orribile. La realtà è molto più tremenda di qualsiasi libro. Ma non possiamo smettere di raccontare e leggere storie, perfino nascosti in un rifugio antiaereo, perfino in fuga dalle nostre case colpite. Nel nostro racconto abbiamo messo in evidenza i più forti meriti del popolo ucraino – il coraggio e l’unità”.

Unfortunately, after a war, not everything can go back to the way it was before … that’s why “Danko still has a web of cracks near his heart, while the tips of Zirka’s wings have remained a little burned and Fabian limps with the leg that he had pointed with the thorns “?

What’s the moral? What do children need to understand?

This war changes everyone of us. We will miss so many people we lost. We will miss our homes, streets and cities. We will rebuild everything with time, but it will never be the same. Many of us will be scared of loud sounds. Many will have scars, on their bodies and on their souls. And we will appreciate the simple things, which we didn’t notice before. And there is no doubt that we will be happy again.

Sfortunatamente, dopo una guerra, non tutto ritorna come prima… ecco perché “Danko ha una raggiera di incrinature vicino al cuore, mentre le punte delle ali di di Zirka sono ancora bruciacchiate e Fabian zoppica con la gamba ferita dagli spini”?

Qual è la morale? Cosa devono capire i bambini?

“Questa guerra ci cambia tutti. Ci mancheranno tante persone che abbiamo perduto. Ci mancherà la nostra casa, le strade e le città. Col tempo ricostruiremo tutto, ma non sarà mai la stessa cosa. Molti di noi avranno paura dei rumori forti. Molti avranno cicatrici, sul corpo e sull’anima. E apprezzeremo le cose semplici, a cui prima non facevamo attenzione. Non c’è dubbio che torneremo a essere felici”.

The poppy has become an international symbol to commemorate the victims of the war.

A fairy tale so that Ukrainian children know and remember the tragic experiences of their homeland, so as not to be overwhelmed, to leave the way open for a new existence. Is this the meaning of your work on children?

“Yes, definitely.

This war makes terrible statistics. During these four weeks of invasion Russians killed 135 Ukrainian children, many got injured. More than 50% of Ukrainian children according to Unisef have become refugees since 24. February 2022. 1,8 millions children moved abroad seeking shelter, 2,5 millions of children moved from their houses ro other regions of Ukraine. So we all, children and adults must remember how strongly we love our home, our family, how strongly connected we are with each other, how we suffered, how we cried, how we fought and how we won, how we were hurt and how we healed. We have to work with our memory, to remember who we are.”

Il papavero è diventato un simbolo internazionale per commemorare le vittime di guerra.

Una favola per far sì che i bambini ucraini sappiano e ricordino le tragiche esperienze della loro patria, per non essere sopraffatti, per lasciare aperta la strada a una nuova esistenza. È questo il significato del vostro lavoro coi bambini?

“Sì, assolutamente. Le statistiche su questa questa guerra sono terribili. Durante queste quattro settimane di invasione i russi hanno ucciso 135 bambini ucraini, e molti sono i feriti. Più del 50% dei bambini ucraini secondo l’Unicef sono diventati rifugiati dal giorno 24 febbraio 2022. 1,8 milioni di bambini hanno cercato rifugio all’estero, 2,5 milioni si sono trasferiti dalle loro case ad altre regioni dell’Ucraina. Quindi tutti noi, bambini e adulti, dobbiamo ricordare quanto forte è il nostro amore per la nostra casa, la nostra famiglia, quanto forte è il legame che ci lega gli uni agli altri, quanto abbiamo sofferto, quanto abbiamo pianto, quanto abbiamo combattuto e infine vinto. Come siamo stati feriti e siamo guariti. Dobbiamo lavorare con la memoria, per ricordare chi siamo”. Continua a leggere→

приходит война – ты не молчи, кричи.

приходит война – ты не молчи, кричи.

Premessa

Premessa

COMMENTO

COMMENTO